CURE Farm Map

Please check out the map areas below to learn how landowners and land managers can enhance different habitat types to benefit species like rabbits, quail, and songbirds that require early succession habitats.

Habitat Management Areas

Forest management activities which improve wildlife habitat may reduce or enhance future economic returns from timber harvests. Landowners must find a balance that satisfies their objectives. Fortunately, many forestry and habitat practices can enhance future economic returns from timber harvests and improve wildlife habitat. Both pine and hardwood forests can provide excellent habitat for wildlife with each possessing not only similar species but also species that are unique to particular habitats.

Pines

Much of the forested uplands in North Carolina have been converted to pine plantations, and this can be a limiting factor for wildlife dependent upon upland pine habitat. While mature natural pine stands maintained by fire typically provide better wildlife habitat, properly managed pine plantations can provide suitable habitat for many wildlife species.

Hardwoods

Hardwood bottom within a Coastal upland pine ecosystem. Hardwood bottom within a Coastal upland pine ecosystem.

The historical expanse of hardwood forestlands in North Carolina varies greatly throughout the state. Most of the mountains are dominated with hardwoods, and this hardwood dominance decreases as one moves east across the state. In the Piedmont and Coast, hardwoods were typically restricted to hardwood bottoms and wetlands due to the presence of frequent fire in the upland areas. This is changing as the historical dominance of pines is fading due to land use and practices in the Piedmont and the Coast Plain.

Site Preparation

When preparing ground for planting trees, site preparation techniques that minimize ground disturbance should be utilized when possible. Habitat friendly site preparation can be achieved through the use of site preparation burns and selective herbicides. Herbicide application can be modified to be less intrusive by using the lowest effective rate, timing use during early growth periods, and by spot or banded application.

Mechanical techniques such as KG blading, root raking, and bedding should be used only when absolutely necessary. Heavy machinery compacts soil which can have negative effects on both timber production and habitat. Bedding negatively effects groundcover due to excessive disturbance and alters hydrology by changing the flow and drainage of water. These activities and heavier applications of herbicides not only cost more but increase the negative impacts on ground cover which is essential for wildlife food and cover.

Planting Pines

The decision of which pine species to plant is best based upon a soils map and the advice of an experienced forester. Planting loblolly in poorly drained soils and longleaf on excessively well drained sands is a simple decision while soils “in-between” can produce quality timber for both loblolly and longleaf. The decision should start by using the pine that is within its natural range. Loblolly’s range includes the Coastal plain and the Piedmont while the range of longleaf is mainly confined to the Coastal plain. While loblolly pines occurred along the Coast, they were historically found along the edges of wetlands, and longleaf dominated the uplands due to frequent fire. The benefits of longleaf pine are increased drought, fire, disease, and insect resistance while loblolly pines usually produce merchantable timber in shorter rotations.

After tree selection, spacing is the next most important consideration for planting pines. Planting at lower densities of 300-400 trees per acre can produce better wildlife habitat (allowing more sunlight into stands for increased production of beneficial groundcover) and timber profits. Stands planted at lower densities produce increased diameter growth, become saw timber sooner, and delay crown closure. Increased survival rates through genetically improved loblolly seedlings and better planting techniques for longleaf have made planting fewer pine seedlings per acre possible. The use of wide rectangular spacing also results in planting at lower densities with decreased machine planting costs, seedling costs, number of rows requiring application of banded herbicide, and allows for selective thinning as opposed to row thinning. After a stand planted at a lower density is harvested, it can result in a higher profit per acre due to increased saw log production and lower establishment costs.

Planting Hardwoods

The most important aspect in planting hardwoods is selecting the right species for the stand. On wet sites, consider willow oak or green ash and in fertile well-drained sites, consider cherrybark oak, shumard oak, swamp chestnut oak, sweetgum, or yellow poplar.

There are several natural methods that can be used to produce a stand of hardwoods. This can be done via seedlings, sprouts, and seed. Residual seedlings that remain after logging can be used to establish a new stand, or seedlings can be planted. Stump sprouting is another possible source of new trees that can grow vigorously after harvest and thus are better able to compete with other vegetation. Some trees with widely dispersed seeds such as yellow poplar and green ash may have seeds present before or just after logging that may contribute substantially to the new tree crop. A determination of potential natural regeneration is required to decide if tree planting will be necessary. If there is an inadequate potential for natural regeneration, saplings or seeds can be purchased. The recommended density for seedlings is 100 to 400 trees per acre.

Hardwood Control in Pines

Prescribed fire applied within a pine stand to promote fire dependent species and to reduce hardwood competition. Prescribed fire applied within a pine stand to promote fire dependent species and to reduce hardwood competition.

Maintaining a pine stand with a lush herbaceous groundcover and an open midstory is essential to many wildlife species. An open midstory is also beneficial to pine trees because it reduces competition from hardwoods and volunteer pines. Prescribed burning in conjunction with herbicides can be used to achieve both wildlife and forestry objectives by controlling hardwood competition, limbing lower branches, and promoting fire dependent plant species that wildlife depend on for food and cover. While the most important aspect of fire is frequency, timing of fire can also be important. Some plants only produce viable seed when burned during the growing season in early summer, and these fires also typically have greater top kill and complete kill of hardwoods. A burn plan that utilizes a mix of dormant and growing season burns is often more beneficial to plants and wildlife.

Specific pine species used will determine how prescribed burning is implemented. Loblolly pines should not be exposed to fire until they are at least 15 feet tall while longleaf pine seedlings can be burned once they reach a root collar diameter of half an inch which typically occurs 6 to 12 months after planting. The negative impacts of burning pine stands are potential mortality and decreased growth while the positive outcome is a reduction of competition which can promote growth. Crown scorch of loblollies is another possible issue with burning that can be minimized by how fire is implemented and by burning during proper weather conditions. Crown scorch can cause stress leading to increased susceptibility to ailments that healthy trees would resist. On the other hand, longleaf pines are much more tolerant of crown scorch than loblollies and will likely recover from heavy scorching.

Another option for hardwood control is the use of herbicides. Herbicides can be a fast and effective way to reduce the number of hardwood stems in a pine stand. Hardwoods that are stifling groundcover can be efficiently reduced, particularly larger hardwoods that are less susceptible to fire. The negative impacts can be significant if desirable plants are reduced or eliminated. Therefore careful consideration and planning must be done to reduce the negative impacts of herbicides on the herbaceous groundcover.

Thinning Pine Stands

Third row thinning of a pine stand with native grasses planted along side of the take rows. Third row thinning of a pine stand with native grasses planted along side of the take rows.

Pine stands managed for timber are typically thinned to a basal area between 60 and 110 square feet per acre, but wildlife generally benefit from stands thinned to a basal area of 60 square feet per acre or less. Pine stands should be thinned early and often to promote growth of crop trees, mast trees, and herbaceous groundcover plants. Thinning has several benefits that include growth being concentrated on higher quality, faster growing trees. This leads to a reduction in time to harvest and an increase in larger high value trees. Commercial thinning also provides income periodically during the life of the stand, and it allows more light to reach the ground which produces more herbaceous groundcover leading to better wildlife habitat.

Pre-commercial thinning is another thinning practice that can be used to reduce stand density in heavily stocked pines. It also increases productivity in longleaf stands that have not been managed with fire by removing loblolly and hardwood competition. Prescribed burning can be an essential natural thinning method for managing longleaf stands. Depending on how fire is applied, it can be used to thin longleaf seedlings to a lower density, or it can reduce the need for manual thinning to remove hardwoods and other pines.

Thinning Hardwoods

Timber and habitat quality can be increased through thinning. A balanced goal of promoting timber and habitat can be achieved by removing trees of undesirable quality. This will concentrate more growth in crop and mast producing trees. Trees with larger crowns will result and thus produce more mast for wildlife. Also, some commercially undesirable trees that have high wildlife values (such as black gum and cherry) should be left. Many game species, including deer, turkeys, grouse, and squirrels will be able to take advantage of increased mast production, and songbirds will be provided with larger diameter trees that may one day provide cavity nests and refuge.

Harvesting

Old growth longleaf pine stand that has undergone periodic selective thinning for overa century. Old growth longleaf pine stand that has undergone periodic selective thinning for overa century.

Harvesting can be used to manage habitat diversity at the landscape level by creating adjoining stands of different age classes and a mixture of forest types for a diversity of habitats that benefit wildlife. Clear cuttingcreates quality habitat for species that require early successional habitat while group and single tree selection maintain habitat for species that require forested habitat. Alternatives to clear cutting such as group selection or single selection decrease how a stand is impacted by logging, but they also typically decrease logging profits. Group selection is essentially a ¼ to ½ acre clear cut while single selection is best used to remove a few high quality trees for products such as saw logs and utility poles. These last two techniques maintain a forested ecosystem that is essential for wildlife dependent upon large stands of mature timber.

Snags and Nest Cavities

Artificial cavity nest box. Old Artificial cavity nest box.

Snags are standing dead or dying trees that are an important source of food, cover, and nesting sites for many wildlife species. While birds such as woodpeckers are obvious users of snags, other wildlife including mammals and reptiles utilize snags and their cavities. Landowners interested in managing snag availability should retain 5 to 6 snags per acre to meet the minimum requirements of wildlife. Ideally a variety of sizes and species should be made available, although larger trees are generally needed for cavity nesting species.

In today’s heavily managed timber stands there is a shortage of snags. Snags can be protected during harvest and thinning by marking existing and potential snags. During prescribed burning, if there is a shortage of snags, the base around a snag can be raked, or the area can be lit prior to a fire reaching the tree. To offset a snag shortage, snags can be created. The easiest way to create a snag is to girdle a tree with a chainsaw. Artificial nest boxes are an effective and relatively inexpensive method to overcome a shortage of large diameter snags for cavity nests. These nest boxes can be used in pine stands on trees that are not of adequate size for wildlife to create natural cavities.

Summary

Wildlife habitat improvements are not only based on what is economically feasible but also on technical guidance available to landowners. There are various sources of guidance available to landowners from government agencies and private contractors. Two such sources of guidance are the North Carolina Department of Forest Resources County Ranger and the Forest Stewardship Biologist of the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission. These two individuals can provide free assistance in managing your land for timber and wildlife. Landowners may also consider hiring a consulting forester. Although consulting foresters have different philosophies regarding timber and wildlife management, one should be chosen based upon management goals.

Introduction

Wise management is the key to healthy and productive pastures. Controlled, rotational, or careful management of intensive grazing has increased forage production for many producers. Landowners that skillfully use livestock to harvest forage can improve soil fertility and promote diverse, dense, and improved pasture ecology. A healthy grazing system with fertile soils and productive pastures will support healthy animals and improved wildlife habitat.

Native Warm Season Grasses

Rotational Grazing Multiple resource benefits cannot be achieved in forage systems with only one grass species or with multiple species that grow at one period during the year. In general, grasses are divided into a cool season category (examples, tall fescue, ryegrass, orchard grass) and a warm season category (examples, Bermuda, big bluestem, yellow indian grass), based on period of active growth. The proper mixture and management of warm and cool season grass in a forage system can produce more forage and provide early successional habitat for wildlife species. Native warm season grasses (NWSG) offer excellent forage quality. Research has shown daily weight gains of 2-4 lbs. for various NWSG species and crude protein levels ranging from 8-16%. This high quality forage is available during the months of June and July when more traditionally used fescue has gone dormant. NWSG grasses are more drought tolerant than most other grasses. The root systems of NWSG can extend 10 feet or more into the soil and reach moisture other grasses cannot, and NWSG require very little fertilizer to be productive.

There are a few considerations when integrating NWSG into a forage system. First of all, areas planted in NWSG should not be grazed or hayed for a year after planting. This allows the plant to establish a healthy root system which will pay off with a more productive and drought-resistant stand in the future. Along the same lines, NWSG should not be grazed or hayed below five inches to ensure stand vigor and health. To provide wildlife benefits, the grass should not be harvested after August 1 and should be managed with a prescribed burn in the spring. This management style will not only provide much needed winter wildlife habitat, but it will also allow the grass to store food in the root system which will lead to more rapid, higher quality spring growth. Taking into account these considerations and the need for year-round forage sources, NWSG conversion should be undertaken in stages and should be only a percentage (25-50%) of the total forage acreage. The total percentage converted should be based on a forage management plan.

NWSG in a pasture system has many wildlife benefits. Since it is grazed at a later date, usually June, it provides better nesting habitat for grassland birds compared to cool season grasses. NWSG also provides cover for small mammals such as cottontail rabbits and provides better winter cover for migrating birds during fall and winter months due to its taller heights. Native warm season grasses such as yellow indian grass, little bluestem, switchgrass, big bluestem, eastern gama grass, and side oats grama provide excellent habitat for many species of wildlife. The erect growth pattern of these grasses form “bunches” instead of lying over and forming mats of dead thatch. This “bunch” structure provides overhead cover but still offers exposed soil and ease of movement along the ground for wildlife species. When properly managed, NWSG stands provide quail and other wildlife with winter cover as well as excellent nesting, brooding, and bedding habitat. Forbs species such as partridge pea, bundle flower, and Kobe lespedeza can be added to NWSG plantings to provide further benefits for early successional wildlife.

Native Warm Season Grasses are similar in many ways compared to other exotic grasses such as tall fescue and Bermuda. They both flourish when the PH is close to 6.0. However, compared to cool season grasses and Bermuda grass, NWSG needs much lower fertilizer amounts; thus saving the landowner a lot of money in maintenance costs through time.

Rotational Grazing

Interest in controlled grazing is increasing throughout the United States. Controlled grazing systems are economically feasible and more easily managed because of developments in fencing and water technology. Paddock design must be based on landscape, land productivity, water availability, and the number and types of animals in the system. Producers need to understand all the technology available before going to the expense of establishing a grazing system. A good way to explore the technology and cost is by comparing prices in catalogs and farm supply stores that sell the materials such as fencing and/or water systems.

Rotational grazing simply involves dividing the pasture into several areas; usually three to six are sufficient. Depending on the number of animals and the species of grass and legumes in the pasture system, grazing should be no closer than three inches for most forages. Native warm season grasses (NWSG) should not be grazed under five inches. When grasses reach this point, landowners should rotate livestock to the next paddock and target the recovery period for 30-35 days before the pasture is again grazed. During periods of heavy growth, some areas may be hayed and the forage stored and stockpiled for supplemental feeding during the later part of summer or winter months.

| Cool Season Grasses and Legumes Grazing Dates | Native Warm Season Grasses Grazing Dates |

| March – June | June - August |

| August – Late October |

Herbicides for Pastures

Managing pasture weeds is a persistent problem that occurs for managers over time. For most pastures, broadleaf weed control is required, and the best results are obtained in early summer when weeds are actively growing or in autumn after precipitation causes renewed fall growth of perennials weeds. Some weeds, particularly deep-rooted perennials such as Canada thistle, may require repeated treatments over time for control. Furthermore, the most important thing to note when using herbicides is to follow the label instructions to stay within the standards of the law and protect livestock.

Reseeding Pastures

When preparing for reseeding a pasture, the manager has two choices for establishment. One choice is the conventional method of plowing and disking the pasture for seed bed preparation, seeding the pasture area, and dragging or cultipacking the area to cover seed. However, due to the length of time, cost, and problem of erosion, this method is not recommended. The best way to reseed a pasture is to use a no-till drill for reseeding (the picture to the right is an example). The landowner should spray the pasture a few days before seeding with a non-selective herbicide such as roundup or a similar generic product before the pasture is drilled. In some cases, simply drill the desired plant seed into the pasture itself. Seeding should be done in April and early May or in late August and September when soil moisture is adequate.

Watering Systems

Landowners today have a number of watering systems available to aid with their pasture management. “Controlled Access Systems” allow livestock to have direct stream access but limits the number of sites. Gravity flow systems, where the water supply is above the water system for livestock, are a good choice when using springs and ponds. Some other choices are electric pumps and solar pumps that operate using electricity from solar power.

The establishment of watering systems in a pasture system can significantly improve water quality. Watering systems can reduce the amount of waste material, nutrients, and sediment that enters into the stream system. Landowners wanting assistance for improving their pastures through fencing practices can get assistance from the Soil and Water Conservation District (SWCD) in their County or the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS).

Fencing

Fencing is the key to pasture management. It allows livestock producer to rotate pastures and control livestock and predators. Many types of fences are used to provide a physical barrier to control livestock. They include the cedar rail, stone, page wire, barb wire, suspension, hinge tensile, and board fences. Livestock farms need at least one exterior fence plus interior fences to allow the farm to be subdivided and gated to move livestock from one paddock to the other.

Moveable fences offer flexibility to a grazing system. Electric fencing offers this versatility and is affective and inexpensive compared to other fence types. Electric fencing does not require a permanent gate reducing the landowners cost.

Fencing also provides great wildlife habitat when used to protect streams and rivers from livestock. Controlling livestock movement and removing them for the riparian areas reduces erosion and improves water quality by eliminating waste. The borders created by protecting these areas provide undisturbed nesting areas for birds, small mammals, and other wildlife species. Landowners can improve these areas, especially for Bobwhite quail, by burning or lightly disking these sites every three years. Furthermore, landowners can also help protect wildlife by mowing these areas outside the nesting season (April 15-September 15) and doing so on a rotational basis every two or three years. Landowners wanting assistance for improving their pastures through fencing practices can get assistance from the SWCD in their County or the NRCS.

Summary

Well managed forage systems which include NWSG contribute significantly to the sustainability of a farm operation and address all aspects of pasture management including rotation strategies, weed control, pasture reseeding, fencing, and watering systems. Wildlife can also be benefited through economically viable practices that allow for wildlife cover and benefit livestock management. The key to integrating wildlife habitat into a livestock production operation is to contact a professional wildlife biologist for technical assistance. Check the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission’s website at for more information.

| Annual and Perennial Wildlife Seed | Native Prairie Meadow Plants | Native Fruit and Mast Producing Trees and Shrubs |

2008 Farm Bill Guide (PDF)

Natural Resource Conservation

Service (NRCS)

NCWRC "Prescribed Burning

Technical Guidance Sheet" (PDF)

NCWRC "Disking Technical

Guidance Sheet" (PDF)

NCWRC "Native Warm Season

Grass Technical Guidance Sheet"

(PDF)

You may be surprised at the answer if you ask your local wildlife biologist this question.

- At best the answer will be a qualified "maybe." Annual food plots are often not what's needed to improve small game populations on a particular property. For example, recent research indicates that if your only management is planting food plots you may actually be harming quail populations by concentrating and exposing them to wild predators and excessive hunting mortality.

- Before you get a firm answer the biologist will make an assessment of the area to determine if adequate nesting, escape, and brood cover is available. Each small game species has needs for a particular kind of food, cover, and shelter which change depending upon the season of the year and the age of the animal. Food plots, when properly located, can meet some of these needs, especially when used in conjunction with other forms of management.

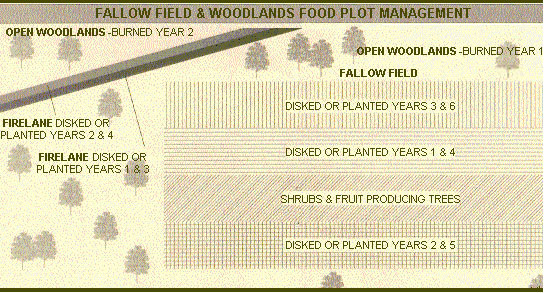

Species such as bobwhite quail, cottontail rabbits, and many other small birds and animals are adapted to survive in the sun-loving, early successional vegetation which follows disturbances by plowing, burning or timbering. Food plots are often planted to benefit these species. But, suitable habitat is also provided by open woodlands that have been prescribed burned, brushy cropfield edges, and land which has recently been fallowed.

ARE YOU COVERED?

- Weedy and brushy areas adjacent to food sources are essential if your food plot is to do more good than harm.

- Use the following guidelines to help make decisions about what, where, when, and if you should plant plots for small game.

- Is there adequate weedy and brushy escape cover nearby? Plots without adequate escape cover nearby may actually harm the species you intended to benefit.

- Bobwhites and rabbits are safer from their enemies if they can feed near cover. Subsequently, plots with a lot of edge are preferred. Square or circular plots have the least amount of edge. Plan plots to be long, narrow and adjacent to escape cover.

- On many farms today, small game populations appear limited mostly by a lack of good breeding cover in the spring and lack of escape cover in the winter-not by a lack of food. Produce nesting and escape cover by rotating your plots. When planting in old fields, move plots annually to create fallow areas of varying ages of weed growth. These fallow areas provide escape cover, nesting cover, and often produce fruits and seeds that compliment the foods produced in the plot.

- Attempt to select good soils for your plantings. Generally, if soils are suitable for rowcrops and produce lush weed crops they will produce good wildlife plantings. Avoid excessively dry or wet sites.

- Consider early spring disking as an alternative to food planting. Disked strips in fallow weed fields (not to exceed 1/3 of the field area) provide good brood habitat. The canopy of young weeds that follow disking produces insects and the patches of bare ground beneath the weeds provide access for broods. Adjacent undisked portions of the field are used for nesting and escape cover. Brood habitat resulting from spring disking is less costly and often equal in quality to that obtained by planting plots.

- Use extensive as well as intensive management. Food plots are an example of intensive management. A great deal of effort is expended on a small area of land. Small game populations w be more responsive if plots are used in combination with more extensive management techniques such as:

| Timber thinning to permit food and cover growth to prosper on the forest floor. | |

| Prescribed bums to set back plant life to the earliest stages. | |

| Strip disking in fallow fields to provide insects, seeds and bare ground throughout the field area. | |

| Conversion of fescue sod to native warm season grasses. | |

| Reduced mowing. Mow only when necessary to prevent trees from overtaking ditchbanks or old fields. Time mowing to occur in early spring, prior to nesting season. |

- Remember, there are no magical formulas for instantly producing an abundance of small game. The broader land uses on an area influence the small game population more than food plots. Where they can be applied, extensive practices can greatly increase populations. After these practices are in place well-planned food plots can provide the "icing on the cake" to facilitate hunting and to provide for specific habitat deficiencies.

- A variety of good planting materials are available commercially. A brief description of one spring and one fall seeding mixture using commonly available seed follows.

ANNUAL MIXTURES FOR SPRING PLANTING

- The following plant materials can be broadcast or row planted on a prepared seed bed from early April in the coastal plains through early June in the mountains. This mixture is resistant to deer browse.

- Good annual mixtures contain strong stalked members of the grass family such as Egyptian Wheat, Sorghum, Milo or Hybrid Pearl Millet. These plants stand well in the winter and provide cover as well as producing seed.

- Browntop Millet, German Millet, and Proso Millet produce good seed quickly and are often used by young birds and rabbits in late summer.

- Kobe and Korean Lespedeza produce good insect populations, browse for rabbits, and a seed that is used by quail in winter.

- The mixture should contain equal parts by weight of the strong stalked grasses, early producing millets, and annual lespedezas. Fertilize and lime according to soil tests. Plant at a rate of 15 lbs. per acre and cover lightly (1/2 inch or less). (Some reseeding of lespedezas will occur so move to a new area to make additional plantings the following summer).

- Where deer populations are low other legumes such as cowpeas or soybeans can be added sparingly to the above mixture.

ANNUAL FALL SMALL GRAIN PLANTING

- Wheat Barley or Rye plantings can benefit quail by providing seeds and insects the following fall and winter. Plantings should be made in late September through November. Prepare a seed bed, and plant at a rate of 50 Ibs. per acre. Fertilize and lime according to soil tests. Topseed with Kobe or Korean Lespedeza at a rate of 10 Ibs. per acre in January or February to 4 increase seed and insect production. (Some reseeding of grains and lespedezas will occur so move to a new area or make additional plantings the following fall).

- A good source for information on locally adapted plant varieties and planking dates is your county office of the Cooperative Extension Service. For additional wildlife technical assistance or wildlife planting materials information contact:

North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission

Wildlife Management Division

1722 Mail Service Center

Raleigh, NC 27699-1722

919 733-7291